Overview

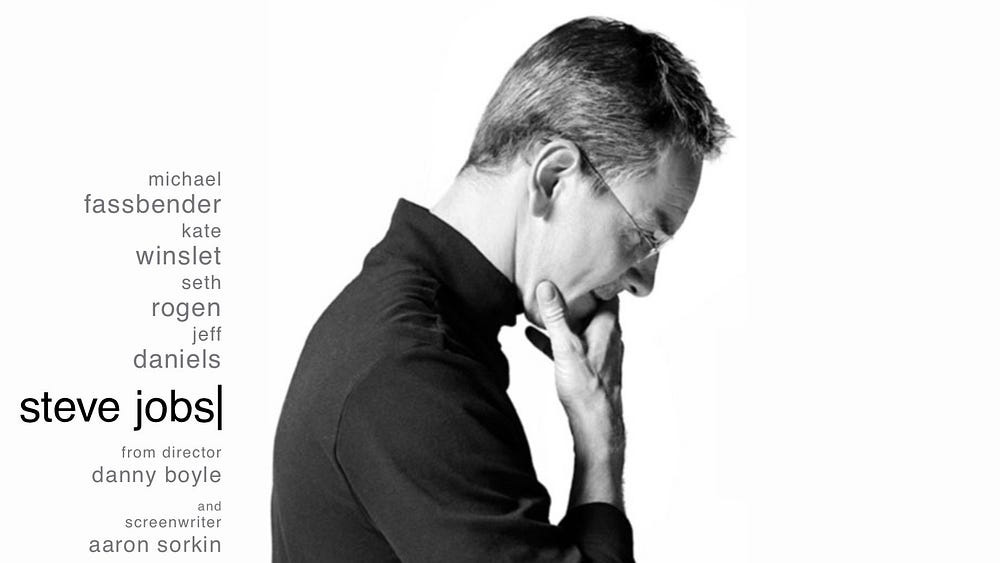

Steve Jobs (2015) is a biopic movie on Steve Jobs shown through various product launches from the Macintosh to the iMac.

Combing Aaron Sorkin’s fiery dialogue with Danny Boyle’s energetic directing style, you get an action movie with words.

The verbal sparring among Jobs and other characters keeps the movie engaging, entertaining, and informative on historical context and character motivations.

Sorkin is famous for his rapid and snappy dialogue but not famous enough for his ability to interweave themes throughout the movie in his dialogue and ending it with a ribbon on top.

This technique is called burying the lead, similar to David Milch’s approach to writing the dialogue for Deadwood seen below.

I want to talk about the theme of Childhood embedded in the movie and how Sorkin uses a question posed within the first 30 min of the movie to create an undercurrent of Jobs’s decisions in the movie and waiting to give us the full explanation in the last 30 min of the movie.

Note: I am speaking only about the character of Steve Jobs from the movie and not the actual person. People are more complicated than any movie could portray in a 2-hour timeframe.

Theme of Childhood

Our childhood impacts our lives in more ways than one.

Silently influencing our decisions until we shine a light on them.

In the movie, there are subtle comparisons between a child and computer with certain phrases and issues being brought up throughout the movie.

“A closed system”

A closed system means no user can go inside and modify the components of the computer. The company which made the computer has complete control from the manufacturing to when it reaches in your hands.

In the opening scene of the movie, Jobs is chastising his engineer, Andy, about fixing a voice demo.

Andy: …. If it’s a hardware problem, we can’t get into the back.

Joanna: Why not?

Andy: You want to tell her, or should I?

Steve: Don’t start with me man.

Joanna: Why can’t he get into the machine?

Andy: You need special tools.

Joanna: What kind of special tools? Just take screwdriver and —

Andy: He didn’t want users to be able to open it. You need special tools.

Already we see one of the features of Apple computers. They need special tools to get into the computer to make any changes. When a customer receives an Apple computer, it comes as is and no modifications can be made.

“Computers aren’t paintings”

This is brought up again in a flashback scene between Steve Jobs & Steve Wozniak where Wozniak argues for modularity and allowing users to switch out components to improve graphics, display, computing power, etc.

Steve is extremely against the idea and says there are only 2 ports accessible to users for modularity: printer and modem.

Woz makes the remark: computers aren’t paintings.

Meaning you should be able to switch out components to create a “painting” you want instead of giving someone a “painting” they cannot change to their liking.

A Child as a Computer:

The previous two sections on “a closed system” and “computers aren’t paintings” are common issues brought up in the movie repeatedly.

And for a good reason. Like a child, you cannot replace the parts. You can’t switch out the parts of a child and build your own.

Why is this important?

In the mind of Steve Jobs’s character, the Macintosh and iMac are his kids.

Allowing people to mutilate his computers and change out parts is horrific. He avoids making the system open and allowing for customization because you cannot do that to a child. Customization of a computer is like giving up a child to Steve.

In isolation this observation is strange until you consider Jobs’s adoption history as mentioned in the movie.

Adoption History

Steve Jobs’s adoption history is brought up 3–4 times in the movie, most of the time in passing as a seemingly throw-away line.

This is an Aaron Sorkin script, and no line is obsolete and is explained by the end of the movie.

“I was given back”

As a newborn, Steve was put up for adoption by his biological parents as he explains in his final conversation with John Scully.

Steve: I was given back…. I don’t know why you’ve always been interested in my adoption history, but you said it’s not like someone looked at me and gave me back…but that is what happened……A lawyer couple adopted me first then gave me back after a month. They changed their mind. Then my parents adopted me. My biological mother had stipulated that whoever adopted me had to be wealthy, college-educated, and Catholic. Paul and Clara Jobs were none of those things, so my biological mother wouldn’t sign the adoption papers.

John Scully: What happened?

Steve: There was a legal battle that went on for a while. My mother said she refused to love me for the first year. Y’know in case they had to give me back.

John Scully: You can’t refuse to love someone Steve.

Steve: Yeah, turns out you can. What the hell could a one-month-old do that’s so bad his parents give him back?

Steve’s life was defined by being given back because of some flaw he didn’t know. He had no control over one of the most important moments of his life and it gnawed at him.

His reasoning for designing the Macintosh and iMac computers, making as closed systems where he has control to how his “child” will grow and makes sure no one can switch out components and give back his “child” becomes clearer.

Though Steve was a one-month-old child, he internalized the stress of the situation in his psyche which guided his decisions in the movie.

Throughout the movie we’re led to believe Steve is being a stubborn man and refusing to change his vision out of ego and desire for fame.

It isn’t until we get to the last 30 minutes that we humanize Steve as a man crippled by his early exposure to indifference and love as a child.

He’s like anyone else.

A person silently indebted to childhood experiences trying their hardest to do some good despite what’s happened to them. and making mistakes and reconciliations along the way.